By Yasin Ali Muhammad

Centrifugation is one of those terms most biology students and researchers encounter early – but few truly understand what’s really happening inside a spinning rotor, or why it matters so much when you’re trying to work with viruses or extracellular vesicles (EVs).

At its core, centrifugation is a physical separation method. It uses centrifugal force to make particles in a sample move through liquid – some faster, some slower, and some barely at all. What actually separates isn’t biology, identity, or function – it’s how fast something sediments under force (Teixeira-Marques et al., 2024).

This article explains what centrifugation does, what limits it, and why it’s so commonly used before any real virus isolation step occurs.

First, the Basics: What Is Centrifugation?

Imagine you tie a ball to a string and whirl it around your head. The ball pulls outward – that’s centrifugal force.

In a lab centrifuge, we spin samples at high speed so particles inside experience a huge outward force*. The heavier and denser the particle, the more strongly it is pushed outward and the faster it sediments – meaning it falls out of suspension and collects at the bottom as a pellet.

But in biological fluids, almost everything floats or sinks at different rates, and many things are similar in size and density. That’s where confusion starts.

How Differential Centrifugation Works

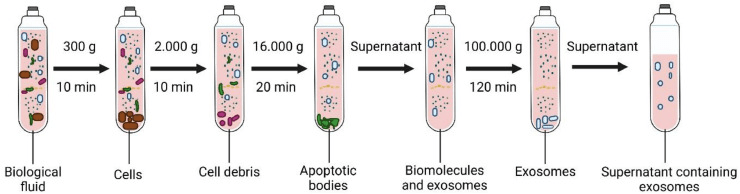

Most labs use a stepwise approach called differential centrifugation:

- Low-speed spin (≈200–3,500 × g)

Removes whole cells and big debris from the fluid. - Intermediate spin (≈10,000–20,000 × g)

Pellets large extracellular vesicles and heavy cell fragments. - High-speed ultracentrifugation (~100,000–200,000 × g)

Used to sediment small EVs (sEVs) and many types of virus particles. - Wash spin

Researchers often resuspend the pellet in buffer (like PBS) and spin again to remove loosely attached contaminants.

Figure 1. Sequential separation of particles from a complex biological fluid This schematic illustrates the sequential separation of particles from a complex biological fluid using increasing centrifugal force. An initial low-speed spin (~300 × g, 10 min) removes intact cells, followed by intermediate centrifugation (~2,000 × g, 10 min) to clear residual cell debris. A higher-speed spin (~16,000 × g, 20 min) pellets larger subcellular structures, including apoptotic bodies. The remaining supernatant contains soluble biomolecules and sEVs. Final ultracentrifugation at very high force (~100,000 × g, 120 min) sediments sEVs, commonly referred to as exosomes, leaving a clarified supernatant depleted of larger particulate material. This process concentrates nanoscale particles based on sedimentation behavior.(Image adapted from Dilsiz, 2024.)

These steps are easy to repeat and scale, which is why centrifugation has become a backbone of preparatory workflows for particles that are far too small to settle on their own – including viruses.

What Differential Centrifugation Is Good At

Differential centrifugation excels at reducing complexity, even if it doesn’t create purity.

It reliably removes large debris early, concentrates small particles that would otherwise remain diluted, and remains accessible to most molecular biology laboratories. This practicality explains why it appears in nearly every virus and EV preparation protocol.

What It Can’t Do on Its Own

This is where many users run into trouble.

1. It separates by sedimentation behavior, not identity

Particles sediment based on size, density, and shape – not because they are viruses, EVs, lipoproteins, or protein complexes. In real biological fluids, many of these particles overlap physically (Saleem et al., 2025).

As a result, sEVs may pellet earlier than expected, some viruses remain in suspension until extreme forces are applied, and non-target components can co-sediment with the particles of interest.

The pellet is therefore a mixture, not a purified fraction (Wantchecon et al., 2025).

2. High centrifugal forces can damage fragile particles

Ultracentrifugation involves forces strong enough to deform biological structures.

Repeated high-speed spins can alter vesicle shape, disrupt lipid membranes, skew size distributions, and reduce biological activity (McNamara et al., 2018). While rigid, non-enveloped viruses often tolerate these conditions well, enveloped and pleomorphic viruses are far more susceptible to mechanical stress.

This limitation applies equally to sEVs, which are particularly sensitive to shear and compression.

3. The EV – virus overlap problem

Viruses and extracellular vesicles frequently occupy the same size and buoyant density ranges. Because differential centrifugation relies purely on physical behavior, this overlap makes co-isolation unavoidable in many contexts.

This is not a technical failure – it is a physical constraint.

As a result, virus preparations often contain EVs, and EV preparations may contain viral particles, especially when working with infected cell cultures or complex fluids (Saleem et al., 2025).

Table 1. A practical comparison of particle performance during ultracentrifugation.

| Particle Type | Typical Traits | Performance in Ultracentrifugation |

|---|---|---|

| Adenovirus | Non-enveloped, rigid capsid | High – structurally robust |

| Bacteriophage T4 | Rigid capsid with tail | High – stable under force |

| Influenza A | Pleomorphic, enveloped | Low – prone to deformation |

| HIV | Enveloped, sensitive | Low – damage likely |

| Small EVs (30–200 nm) | Lipid bilayer, shear-sensitive | Low – easily distorted |

| Large EVs (100–1000 nm) | Larger vesicles | Moderate – more resistant |

How Density Gradients Try to Improve Separation

To increase selectivity, centrifugation can be paired with density gradients, a refinement known as density gradient centrifugation (DGC).

In density gradient centrifugation, particle movement depends on the difference between a particle’s density and that of the surrounding medium. A particle denser than the medium sediments toward the bottom of the tube under centrifugal force, while a particle less dense moves upward, toward the axis of rotation.

How the gradient is constructed determines what property drives separation.

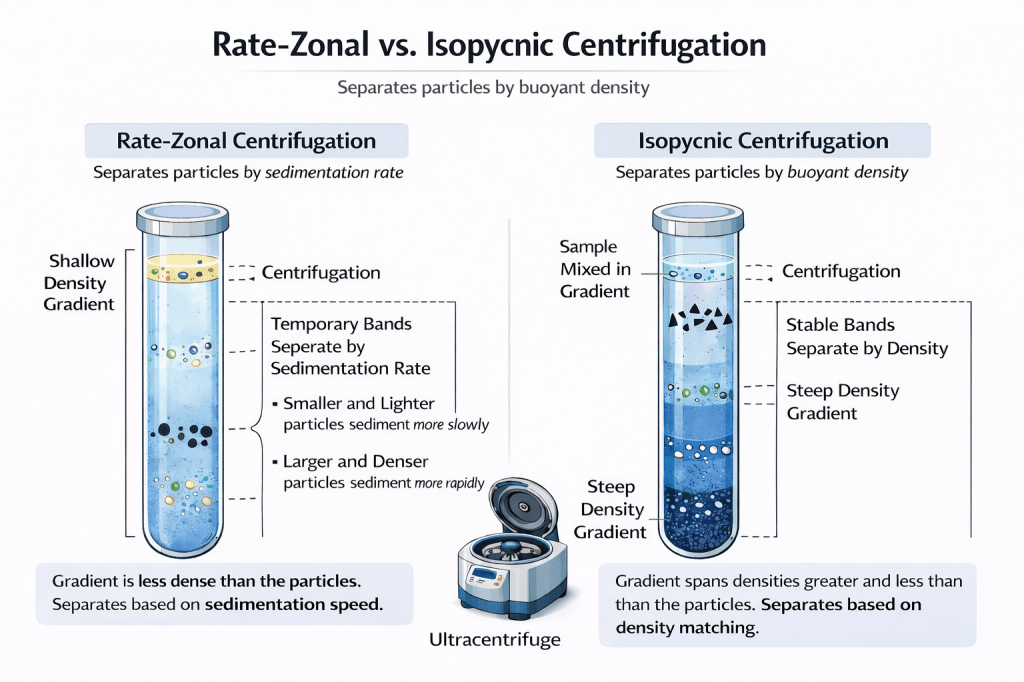

Rate-zonal centrifugation

Rate-zonal centrifugation separates particles according to their sedimentation rate-how quickly they move through a medium under centrifugal force. This approach uses shallow density gradients, which stabilize the sample without matching particle density.

The sample is layered as a narrow band on top of a pre-formed gradient, most commonly made from sucrose or Ficoll. Importantly, the gradient is always less dense than the particles being separated, meaning all particles will eventually sediment if centrifugation continues long enough.

Larger and denser particles migrate more rapidly through the gradient, while smaller and lighter particles move more slowly, forming temporary bands or zones. Because prolonged centrifugation would cause all particles to pellet at the bottom, the run must be stopped before equilibrium is reached.

Isopycnic (equilibrium) centrifugation

Isopycnic centrifugation separates particles solely by buoyant density, independent of their size or shape. This method uses steep density gradients composed of dense media such as cesium chloride, iodixanol, or Percoll.

Figure 2. Conceptual comparison of rate-zonal and isopycnic density gradient centrifugation. This schematic contrasts two gradient-based centrifugation strategies used to separate biological particles. In rate-zonal centrifugation (left), particles are layered on top of a shallow density gradient that is less dense than the particles themselves. Separation occurs because particles migrate at different speeds under centrifugal force, forming temporary bands based on sedimentation rate. Larger and denser particles move more rapidly, while smaller and lighter particles lag behind, requiring centrifugation to be stopped before equilibrium is reached. In isopycnic centrifugation (right), particles are distributed within a steep density gradient that spans densities both greater and less than those of the particles. During centrifugation, each particle migrates until it reaches its isopycnic point, where its density matches that of the surrounding medium, forming stable, sharply defined bands that persist even with prolonged centrifugation.

In this case, the gradient spans densities both greater than and less than those of the particles. During centrifugation, each particle migrates until it reaches its isopycnic point – the position where its density exactly matches that of the surrounding medium.

Once this point is reached, the particle stops moving, even if centrifugation continues. As a result, isopycnic centrifugation produces stable, sharply defined bands determined by density rather than migration speed.

Why gradients still fall short

Many viral particles share buoyant density ranges with extracellular vesicles, including sEVs and microvesicles. As a result, even carefully optimized density gradients are often insufficient to definitively resolve viruses from EVs (Marca et al., 2025).

While density gradient centrifugation can yield highly concentrated isolates, this frequently occurs at the expense of compositional purity, particularly when working with infected cell cultures or complex biological fluids where viral and vesicular particles co-migrate (McNamara et al., 2020).

*Here’s a brief video you asked about showing how centrifugation works – and a short explanation to go with it: https://youtu.be/THkhODsTjxY?si=imgp7rsjeVR7GQiL

Takeaway

Centrifugation – with or without density gradients – is a powerful preparative tool in virus isolation, but it is not a guarantee of biological purity. In the articles that follow, we’ll examine additional preparative approaches as well as techniques specifically designed to improve selectivity and enhance sample purity.

References

Dilsiz N. (2024). A comprehensive review on recent advances in exosome isolation and characterization: Toward clinical applications. Translational oncology, 50, 102121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranon.2024.102121

Marca, R. D., Giugliano, R., Zannella, C., Acunzo, M., Parimal, P., Mali, A., Chianese, A., Iovane, V., Galdiero, M., & De Filippis, A. (2025). Role of exosomes in viral infections: a narrative review. Virus research, 361, 199644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2025.199644

McNamara, R. P., Caro-Vegas, C. P., Costantini, L. M., Landis, J. T., Griffith, J. D., Damania, B. A., & Dittmer, D. P. (2018). Large-scale, cross-flow based isolation of highly pure and endocytosis-competent extracellular vesicles. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, 7(1), 1541396. https://doi.org/10.1080/20013078.2018.1541396

McNamara, R. P., & Dittmer, D. P. (2020). Modern techniques for the isolation of extracellular vesicles and viruses. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology, 15(3), 459–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11481-019-09874-x

Saleem, M., Chang, C. W., Qadeer, A., Asiri, M., Alzahrani, F. M., Alzahrani, K. J., Alsharif, K. F., Chen, C. C., & Hussain, S. (2025). The emerging role of extracellular vesicles in viral transmission and immune evasion. Frontiers in immunology, 16, 1634758. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1634758

Teixeira-Marques, A., Monteiro-Reis, S., Montezuma, D., & others. (2024). Improved recovery of urinary small extracellular vesicles by differential ultracentrifugation. Scientific Reports, 14, 12267. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62783-9

Wantchecon, A., Boucher, J., Rabezanahary, H., Gilbert, C., & Baz, M. (2025). Comparative Analysis of Extracellular Vesicle and Virus Co-Purified Fractions Produced by Contemporary Influenza A and B Viruses in Different Human Cell Lines. Viruses, 17(11), 1470. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17111470

Yasin Ali Muhammad holds a bachelor’s degree in Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology from Georgia State University. During his undergraduate training, he studied in a laboratory focused on the pathogenesis of mouse hepatitis virus (MHV), a widely used model for human coronaviruses. In addition to his laboratory experience, he has authored multiple peer-reviewed publications in virology, reproductive biology, neurobiology, and related biomedical fields.

Leave a comment