By Yasin Ali Muhammad

Reproductive physiology is often taught as a simple top-down process: the brain releases hormones, the ovaries respond, and the menstrual cycle unfolds on schedule. While this explanation works as an introduction, it misses the most important feature of the system – reproduction is governed by feedback, not commands.

At its core, reproductive function depends on constant two-way communication between the brain and the ovaries. This communication allows the body to adjust hormone release in real time, ensuring that ovulation occurs only when conditions are optimal.

The Basic Framework: The Hypothalamic–Pituitary-Gonadal Axis

The coordination between the brain and the ovaries is commonly presented in a simplified, stepwise manner. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is released from the hypothalamus and stimulates the anterior pituitary to secrete two key hormones: luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). LH is responsible for triggering ovulation and supporting progesterone production following ovulation, while FSH promotes the growth of ovarian follicles and stimulates estrogen synthesis. The ovaries, in turn, produce estradiol and progesterone, which relay feedback signals back to the brain to regulate this process.

For most of the menstrual cycle, estradiol operates through negative feedback. Moderate estradiol levels signal the hypothalamus and pituitary to restrain GnRH, FSH, and LH release. This prevents excessive follicle recruitment and maintains orderly follicular development. This phase is characterized by:

- Pulsatile GnRH release

- Moderate FSH and LH secretion

- Controlled estrogen production

Negative feedback keeps the system stable and prevents premature ovulation.

As a dominant follicle matures, estradiol levels rise progressively. Around the middle of the menstrual cycle – typically about 10 to 14 days after the onset of menstruation, just prior to ovulation – estradiol concentrations reach a critical threshold and remain elevated for a sustained period (Reed & Carr, 2018). At this point, estradiol’s effect on the brain switches from negative to positive feedback (Kauffman, 2022).

This transition activates a specialized population of hypothalamic neurons that shift GnRH secretion from a low-frequency, tonic pattern to a high-frequency pulsatile mode that preferentially drives LH release (Coss, 2018). The resulting pre-ovulatory surge in luteinizing hormone (LH) causes rupture of the dominant follicle and release of the oocyte, marking ovulation.

Kisspeptin Neurons: The Key Intermediaries

Estradiol does not act directly on GnRH neurons alone. Instead, it primarily influences kisspeptin-producing neurons, which serve as the main upstream regulators of GnRH (Muhammad, 2025).

There are two functionally distinct kisspeptin populations (Uenoyama et al., 2021):

- Arcuate nucleus (ARC) KNDy neurons, which regulate pulsatile GnRH release and mediate negative feedback

- Rostral periventricular (RP3V/AVPV) kisspeptin neurons, which mediate estradiol-induced positive feedback and generate the LH surge.

Neurotransmitters Fine-Tune the Signal

In addition to hormonal regulation, reproductive control relies heavily on classical neurotransmission. Hormonal feedback is layered on top of neural signaling, allowing for precise, moment-to-moment regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons. Two neurotransmitters are especially important in this process: glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).

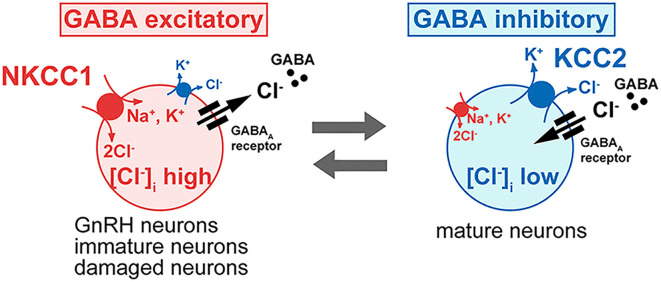

Glutamate provides excitatory drive within the reproductive axis, particularly by stimulating kisspeptin neurons involved in ovulation (Wang et al., 2018). GABA, by contrast, plays a context-dependent role that is primarily determined by GABA-A receptor–mediated signaling. GABA-A receptors are ligand-gated ion channels that directly influence neuronal membrane potential by permitting chloride (Cl⁻) movement across the membrane (Mihaylov et al., 2025;Zhu et al., 2022). Whether this produces inhibition or excitation depends not on GABA itself, but on the intracellular chloride gradient (Watanabe et al., 2014).

That chloride gradient is established by the relative proponderance of two cotransporters: the Na⁺–K⁺–2Cl⁻ cotransporter (NKCC1), which increases intracellular chloride, and the K⁺–Cl⁻ cotransporter (KCC2), which extrudes chloride from the cell. In most mature neurons, dominant KCC2 activity maintains low intracellular chloride levels, so GABA-A receptor activation allows chloride to enter the cell, leading to hyperpolarization and suppression of neuronal firing. GnRH neurons, however, exhibit comparatively higher NKCC1 activity and reduced KCC2 influence, resulting in elevated intracellular chloride concentrations (Watanabe et al., 2014).

Figure 1. Influence of Intracellular Chloride on GABA-A Receptor Function in GnRH Neurons. Intracellular chloride (Cl⁻) levels determine if GABA-A receptor activation is inhibitory or excitatory. In most neurons, low Cl⁻ leads to chloride influx, causing hyperpolarization and inhibition. In GnRH neurons, high intracellular Cl⁻ enables chloride efflux, resulting in membrane depolarization and increased excitability. This change in GABA signaling is crucial for GnRH neuron activation and reproductive hormone release. (Adapted from Watanabe et al., 2014.)

As a consequence, activation of GABA-A receptors in GnRH neurons promotes chloride efflux rather than influx, producing membrane depolarization instead of hyperpolarization. This depolarizing response increases neuronal excitability and converts what is typically an inhibitory neurotransmitter into an excitatory signal in these cells, enabling rapid, moment-to-moment modulation of GnRH activity.

Together, this transporter-driven GABA-A signaling and excitatory glutamatergic input, allows GnRH neurons to integrate multiple neural signals and finely regulate reproductive hormone release.

The Takeaway

The reproductive axis does not function like an on-off switch. Instead, it operates as a dynamic control system that continuously adjusts itself in response to both hormonal feedback and neural context. Negative feedback mechanisms preserve stability across most of the cycle, while positive feedback enables decisive transitions, such as the shift that culminates in ovulation. Neural intermediaries provide the precision needed to translate these hormonal signals into appropriately timed physiological responses.

Reproductive physiology therefore depends on feedback loops rather than linear instructions. The hypothalamus and ovaries are engaged in constant two-way communication, using hormones, neuropeptides, and neurotransmitters to regulate the timing, intensity, and coordination of reproductive events.

Viewed through this lens, ovulation is not a simple hormonal trigger but the outcome of carefully coordinated signaling across interconnected endocrine and neural networks. Understanding reproduction as a self-regulating system-rather than a rigid command hierarchy-makes the elegance and robustness of the menstrual cycle far easier to appreciate.

References

Coss D. (2018). Regulation of reproduction via tight control of gonadotropin hormone levels. Molecular and cellular endocrinology, 463, 116–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2017.03.022

Kauffman A. S. (2022). Neuroendocrine mechanisms underlying estrogen positive feedback and the LH surge. Frontiers in neuroscience, 16, 953252. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.953252

Muhammad Y. A. (2025). Reproductive aging in biological females: mechanisms and immediate consequences. Frontiers in endocrinology, 16, 1658592. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2025.1658592

Reed BG, Carr BR. The Normal Menstrual Cycle and the Control of Ovulation. [Updated 2018 Aug 5]. In: Feingold KR, Adler RA, Ahmed SF, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279054/

Uenoyama, Y., Nagae, M., Tsuchida, H., Inoue, N., & Tsukamura, H. (2021). Role of KNDy Neurons Expressing Kisspeptin, Neurokinin B, and Dynorphin A as a GnRH Pulse Generator Controlling Mammalian Reproduction. Frontiers in endocrinology, 12, 724632. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.724632

Wang, L., Burger, L. L., Greenwald-Yarnell, M. L., Myers, M. G., Jr, & Moenter, S. M. (2018). Glutamatergic Transmission to Hypothalamic Kisspeptin Neurons Is Differentially Regulated by Estradiol through Estrogen Receptor α in Adult Female Mice. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 38(5), 1061–1072. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2428-17.2017

Watanabe, M., Fukuda, A., & Nabekura, J. (2014). The role of GABA in the regulation of GnRH neurons. Frontiers in neuroscience, 8, 387. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2014.00387

Zhu, S., Sridhar, A., Teng, J., Howard, R. J., Lindahl, E., & Hibbs, R. E. (2022). Structural and dynamic mechanisms of GABAA receptor modulators with opposing activities. Nature communications, 13(1), 4582. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-32212-4

Yasin Ali Muhammad holds a bachelor’s degree in Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology from Georgia State University. During his undergraduate training, he studied in a laboratory focused on the pathogenesis of mouse hepatitis virus (MHV), a widely used model for human coronaviruses. In addition to his laboratory experience, he has authored multiple peer-reviewed publications in virology, reproductive biology, neurobiology, and related biomedical fields.

Leave a comment